Mary Paley grew up in a rose-covered country rectory in Northamptonshire, England. Her great-grandfather was the famous philosopher William Paley, who wrote Natural Theology. Unusually for the time Mary’s father, the Reverend Thomas Paley, did not see why his daughter’s education should stop at age thirteen. He taught her maths and science himself and encouraged her to take the new exam for women wanting to become teachers. Mary did so well in it that in 1871 she was offered a scholarship to study at Newnham College in Cambridge.

She was one of only a handful of women students at Cambridge at that time. One of her lecturers was Alfred Marshall, a strong supporter of women’s higher education. His brilliant lectures on political economy inspired Mary and with his encouragement and help she took the university’s final exams, which no woman had ever done before. She passed with honours, although unofficially, because for many years women were not permitted Cambridge or Oxford degrees.

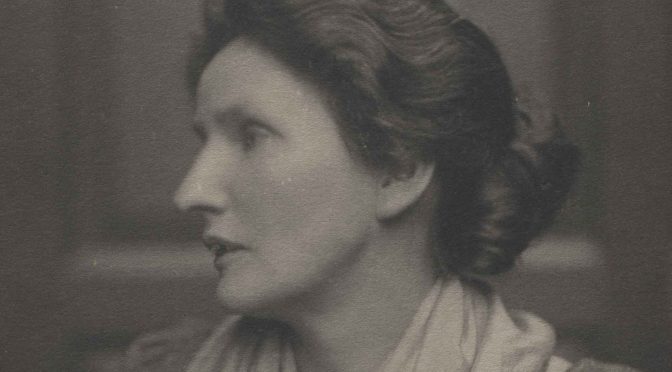

Reproduced with permission of the Marshall Librarian, Marshall Library Archive: Marshall Papers Box 10 (call number 10/7/23)

In 1875 Mary became Cambridge’s first woman lecturer, teaching economics at Newnham College. She was an inspiring teacher who dressed like the women in the Pre-Raphaelite prints that decorated her room. Her students adored her. At the age of twenty-five Mary Paley was that rare thing in Victorian times, an unmarried woman who lived independently from her parents and earned a good living doing a job she loved.

In 1876 she and Alfred married. They both agreed that there should be no promise for her to obey in their wedding service. Their marriage would be an equal partnership, and they both took up university posts at Bristol. They wrote an economics book together, The Economics of Industry (1879) and Mary was a dedicated lecturer who was much loved by her students.

They moved back to Cambridge in 1884 when Alfred was made professor. There were no children. Alfred published a book The Principles of Economy (1890) which was so successful that he decided that the ‘little book’ that he had written with Mary was not good enough. He told the publisher to print no more copies of it even though it was still selling well and was popular with students. Mary kept her feelings about this to herself.

Even worse, Alfred had changed his mind about women students at Cambridge. He wrote pamphlets and letters objecting to a mixed university, and in 1897 a university law was passed preventing women from being given a Cambridge degree. This did not change until 1947, making it the last university in the UK to give women degrees.

Mary was loyal to Alfred and did not complain, but she kept on teaching and inspiring her women students at Newnham and Girton until 1916. She took up painting, revealing a hidden talent, and was an active worker for local charities.

She helped Alfred to write his books and did not publish any more of her own. When he died in 1924 she began a remarkable new career. She used her own money to help to establish the Marshall Library of Economics at Cambridge, and at the age of 75 went to work there as a librarian. Every weekday morning she cycled to work wearing her ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ sandals. She sat at the library’s front desk, greeting each student by name and offering advice about books. The historian G.M. Trevelyan wrote that ‘nothing escaped her clear, penetrating and truthful eye’.

Reproduced with permission of the Marshall Librarian, Marshall Library Archive: Marshall Papers Box 10 (call number 10/4/28)

Mary only reluctantly stopped working at the age of 87 when her doctor insisted on it. She left behind a well-stocked and catalogued library. Today her portrait hangs opposite Alfred’s over the Marshall library staircase. With her penetrating and caring gaze, she watches over each new generation of students, now men and women equally, that through her work she continues to help.

Written for Sheroes of History by Ann Kennedy Smith. Ann is researching the lives of Cambridge’s first university wives.

Find out more…

Read more about Mary’s later career as a librarian on Ann’s blog here.

You can find out more about the Marshall library here.

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.